7 things you should know about Shetland’s history

Jarlshof, South Mainland

Shetland is not a faraway backwater

Shetland, far from being a remote and insular outpost of the British Isles, is well-connected, with a forward-thinking, entrepreneurial spirit and a vibrant and friendly local community. Historically, Shetland has sat on some of the world’s most important trade routes and, over the years, we have seen East Indie merchant ships, Viking and Norse longships, Hanseatic traders, whaling ships on route to the north, Spanish Armada ships and more.

Shetland was once part of the wider Viking world, and many of the Norse influences can still be observed in Shetland today, mostly in the place names and language that were left behind.

By the start of the 14th century, the Hanseatic League, a powerful commercial and defensive confederation of market towns in north Germany, was growing in power and influence, controlling much of the trade in fish and other commodities throughout Europe. Shetland had strong links with Hanseatic traders, best seen in the Hanseatic Bӧd in Whalsay, which is open to visitors throughout the year.

Hanseatic Bod, Whalsay

With the lessening grip of Norway, independent German (or Dutch) merchants were able to come to Shetland and trade directly with the local fishermen for fish, in exchange for currency and other commodities such as hemp, fishing lines, tobacco and flour. This was a lucrative time for local fishermen and these merchants, and by the early 16th century, they were numerous across the isles. This trade saw the growth of Lerwick as a town, and its development into the islands’ capital.

For about 500 years, the Hanseatic League and later the independent merchants had been Shetland's main trading partners – albeit for a time via Bergen – but this trade came to an abrupt end following the 1707 Treaty of Union (between Scotland and England) and the introduction of a ban on the import of foreign salt. The ban on imported salt and a subsequent salt tax (1712) drove the German merchants out, as it was no longer financially viable for them to trade in Shetland.

In 1588, Shetland played an unlikely role in the fate of the Spanish Armada when El Gran Grifón, wrecked in Fair Isle. The Armada ran into bad weather, driving several boats north, including El Gran Grifón, stranding hundreds of sailors on the island, and it has been suggested that the bold and colourful designs of Fair Isle knitwear were learned from the Spaniards who were shipwrecked here. South Harbour’s cemetery, at the southern point of the island, contains the “Spainnarts' Graves”, a mass grave allegedly containing the remains of 50 Spanish sailors from the ill-fated El Gran Grifón.

During the 17th and 18th centuries, trading companies were involved in the lucrative spice and silk trade, selling to culture-hungry Europeans. The Dutch enjoyed a monopoly, making the Netherlands one of the most successful trading nations in the world. Often choosing the “achter om” (north about) route around Britain to avoid conflict in the English Channel, they often sailed around Shetland. Many ran into bad weather, resulting in 27 losses around Shetland waters. Both De Liefde and Kennemerland were lost off the Skerries coast, with the resulting finds including gold and silver coins and Bellarmine jugs, and artefacts varying in size from the tiny peppercorns so central to their voyage to the great cannons used to protect the ships from attack. De Liefde was lost on the east side of Mio Ness, and Kennemerland was lost off Stoura Stack, Grunay. One of De Liefde’s cannons can still be seen outside one of the houses in Housay.

De Liefde cannon in Skerries

Lerwick, Shetland’s main town, owes its very existence to foreign trade. The area now known as Lerwick first became a busy port in the 1500s, when Dutch fishermen used the sheltered confines of Bressay Sound to anchor their boats for their annual summer herring fishery at Johnsmas (24th June). Hundreds of Dutch vessels, known as busses, congregated each summer in the sheltered sound, awaiting the beginning of this lucrative fishery.

In the early days, there were no trade opportunities in Bressay Sound and the area of poor land was used only for animal grazing. The Dutchmen would come ashore and walk a few miles south-west to a spot near Gulberwick called the Hollander’s Knowe to trade. This was relatively short-lived as, by the early 17th century, entrepreneurial islanders were setting up shop on the shores of Bressay Sound – or Buishaven, as it was known to the Dutch – bringing their products to the market. Locals recognised that the Dutch provided a ready market and began trading their knitwear and fresh provisions in exchange for gin, brandy and tobacco. This often illicit trade gave rise to the town that we see today, which is said to have been built by smugglers. Even today, Lerwick Harbour welcomes vessels from all over the world into its sheltered confines.

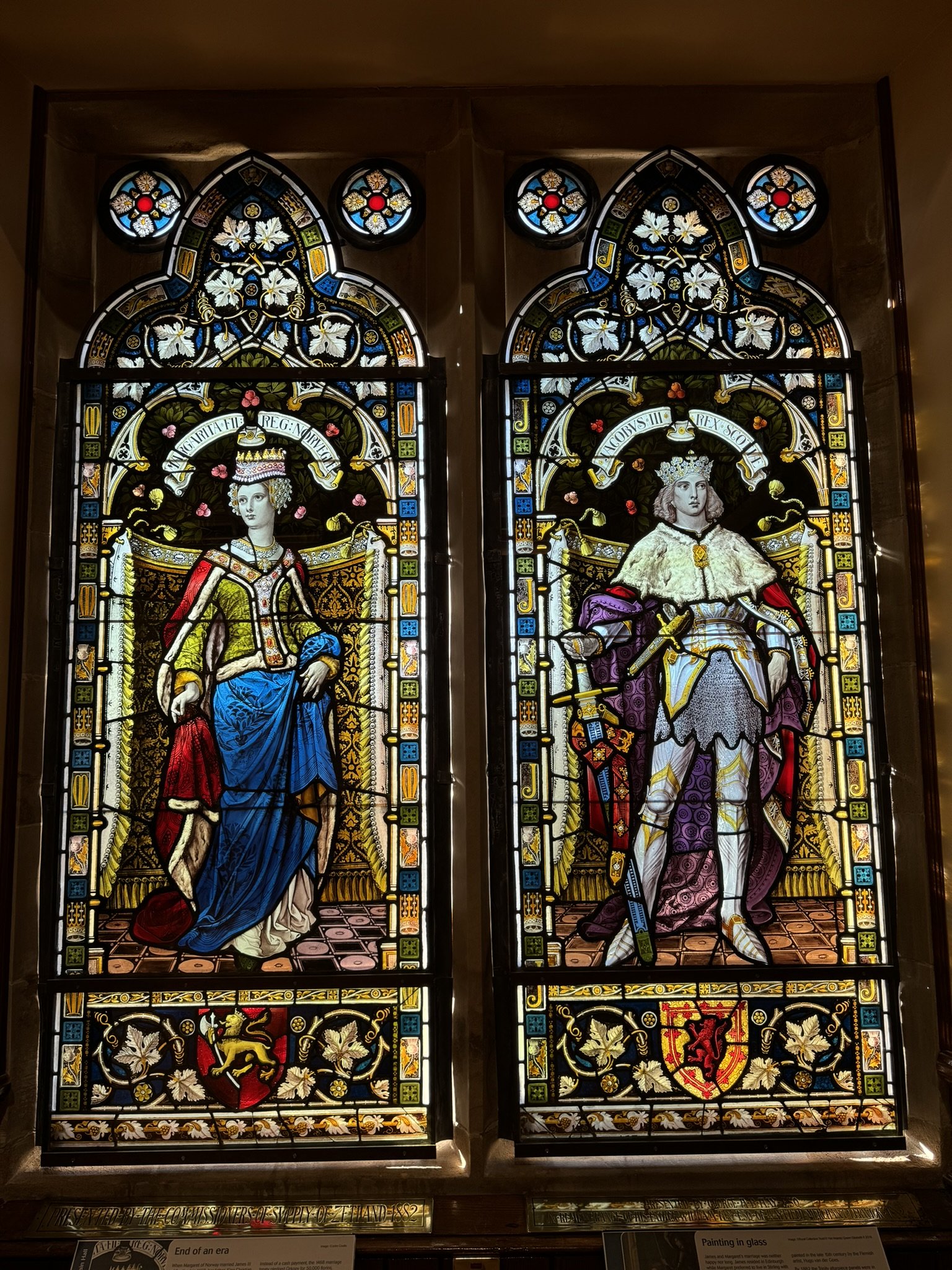

‘The Marriage Window’ in Lerwick Town Hall

Shetland belonged to Scandinavia until 1469

The differences between Shetland and the rest of Scotland can be quite striking. Many visitors arrive here expecting the full Scottish treatment – haggis, kilts and bagpipes – and are surprised to find that Shetland has only been part of Scotland for some 550 years.

The Vikings are thought to have arrived in Shetland from western Norway about 850 AD and subsequently settled in the islands, giving rise to what is known as the Norse Period. Both Shetland and Orkney became Viking, and later Norse, strongholds until 1469 when the rule was pledged to Scotland, bringing a close to more than 600 years of Norse rule.

The period of Norse administration came to an end in 1469, when King Christian I of Denmark sanctioned the marriage of his daughter, Princess Margaret, to King James III of Scotland. What was to happen next would prove to be one of the most important turning points in the islands’ history.

It was hoped that a union between Scotland and Denmark would reconcile differences that had almost set the two countries at war. Scotland was in arrears to the Norwegian Crown (presided over by the Danish King Christian) and paid back the “Annual of Norway” for several years. The marriage condition was a debt write-off: 100,000 crowns for the wedding and the islands of Orkney and Shetland.

King Christian was keen to retain Orkney and Shetland. He abolished the arrears, pledging 60,000 Rheingulden (gold florins from the Rhineland, a popular currency in Northern Europe at this time) as a wedding dowry instead.

Unfortunately, King Christian couldn’t afford to pay the dowry, and with the wedding set for 1469, he pawned Orkney and Shetland. The price set against each island was: Orkney 50,000 florins and Shetland a mere 8,000 florins. Slightly insulting, although understandable given Orkney’s farming credentials. Shetland was very much bolted on to the end of the deal, with Orkney as the more significant asset, when the king failed to raise the cash any other way.

Want more from Shetland? Pick up a copy of my Guidebook today.

Discover hidden gems and rich history with our guidebook. Navigate like a local to find the best scenic spots, and cultural highlights. Our maps, itineraries, recommendations, and tips ensure you make the most of your time, whether you're a first-time visitor or returning. Purchase our guidebook today for a memorable journey. Your perfect trip starts here.

The first people to arrive here came in the Mesolithic

Shetland has been permanently inhabited since Neolithic times (4,000-6,000 years ago) with sites such as Jarlshof, in the South Mainland, and Stanydale Temple, in the West Mainland, offering a glimpse into the lives of early settlers. However, people have been using the islands since Mesolithic times (c. 6,000 years ago). Mesolithic (Middle Stone Age) eras are characterised by human activity and the use of small worked stone tools such as arrowheads and spears. Mesolithic people were generally hunter-gatherers living in small groups and moving around in search of food supplies. Following the seasons and a route that would lead them to food, they would erect temporary shelters before moving on to another place. Evidence from the Mesolithic period in Shetland was very scant until 2002, when a midden containing shells and bones was discovered at West Voe Beach in Sumburgh.

West Voe Beach, South Mainland

Shetland’s first visitors and subsequent settlers are believed to have arrived from the north of Scotland, crossing the Pentland Firth and the North Sea in small open boats formed by stretching animal skins over simple wooden frames. Navigating by eye, these early people kept land in sight, island-hopping north across open water.

These first people would have met with a very different Shetland to the nearly treeless land of today. The islands back then were blanketed in woodland: low-growing hazel, birch and willow. Combined with a more temperate climate, conditions were more favourable, attracting those first Neolithic settlers who could farm at a higher altitude. Many archaeological remains are found deep inland or buried in peat. Around half of the islands today are covered in blanket peat moor, which means that it’s unlikely we’ll ever find much more of Shetland’s Neolithic past, as much of what they left remains unearthed and locked into the hills.

Shetland’s diaspora stretches all around the world

Emigration in the 19th century scattered Shetlanders to all corners of the world, and people left the islands for many reasons. Many left due to land pressure and the effect of the clearances, some left to build a better and brighter future in the New World, and others found that life had just become too difficult at home, with a burgeoning population and the threat of famine putting pressure on families, and starvation a very real threat to existence.

Shetland’s transition into Scotland had not always been an easy one, with characters such as the Stewart Lairds placing economic burdens on people, and an influx of Scottish landowners making changes to traditional land management.

To better understand the ramifications of changes in land use at the hands of the ruling class, it’s important to understand how people in Shetland lived during the 18th and 19th centuries.

The majority of Shetlanders subsisted off the land, taking all they needed to live from the hills and sea that surrounded them. Almost everything that was consumed on the croft, or smallholding, was produced within a few short miles of the home.

Homes were built in the traditional but-an’-ben style: single-storey, two-room houses with adjacent byre and barn, like the Crofthouse Museum in Dunrossness. These homes were traditional in Shetland right into the 20th century and are stylistically similar to the Viking or Norse longhouses that came with the arrival of the Vikings from the 9th century.

Shetland Crofthouse Museum, Dunrossness

Surrounding the croft, land was worked in a runrig system, a land division system that meant each croft had a fair share of good and bad land to work, growing grain crops, cabbage (known as kail) and, later, potatoes.

The precarious societal structure and the absolute power held by local lairds ultimately led to the events of the 19th century: soaring population levels, large-scale land clearances and mass emigration. Eventually the Crofters Holdings (Scotland) Act of 1886 brought a new dawn of hope for Shetland, but the preceding turmoil means that the islands now have a vast diaspora, spanning the globe. In 2010, Shetland held a “Hamefarin” (homecoming), welcoming Shetlanders from all around the world back to their home islands.

Much of Shetland life remained relatively unchanged right up until the dawn of the oil industry in the 1970s, which brought many changes and wealth to the islands, drawing them into the modern era. Prior to this, Shetlanders were governed by the cyclical nature of the seasons, living from the bounty of the land and sea.

Fishing was, and remains, the backbone of the local economy

Economically, Shetland has a thriving economy built around fishing, aquaculture, oil, tourism and farming. Historically, fishing has been the backbone of the economy, and it still supports a multitude of jobs at sea and on land. In more recent times, much of the island’s wealth and infrastructure has been funded by revenue from the oil industry that came to Shetland in the 1970s, however the fishing and aquaculture industries still make up half of the local economic output of the islands (with oil and gas at around 15%). With two state-of-the-art fish markets, one in Lerwick and the other in Scalloway, there are more fish landed in Shetland (population 23,000) than in the whole of England, Wales and Northern Ireland combined, with their population of 61 million.

Lerwick Fish Market

We don’t speak Gaelic. Norn, a form of Old Norse, was spoken in Shetland until a few hundred years ago

Shaetlan’, the language spoken by many Shetlanders, is a regional dialect of the English or Scots language. Rather than being related to the Gaelic spoken elsewhere in Scotland, its roots are firmly embedded in Shetland’s Scandinavian past.

Historically, the language used in Shetland was Norn, a form of Old Norse. Old Norse was spoken throughout Scandinavia, with the closest surviving language today found in Iceland. Each country had its own version of the language, and in Shetland, this developed into Norn.

Despite integration into Scotland, Shetland was slow to let go of its native tongue. Even in the late 19th century, some 400 years since Scandinavian ties were cut, remnants of this old Norse language could still be found, and the last person believed to have spoken Norn in Shetland was Jeannie Ratter, who died in 1926.

The Faroese scholar Jakob Jakobsen, who came to Shetland at the end of the 19th century, recorded all the Norn words he heard spoken and those that were remembered. He travelled all over the islands and compiled these words into a two-volume dictionary of more than 10,000 words. His book Etymological Dictionary of the Norn Language in Shetland (1928) remains, to this day, the greatest work on the dialect ever undertaken.

Many of the dialect words in use today have their roots in the Old Norse language, and 95 percent of Shetland’s place names are Norse. These words and the distinct language spoken in the isles gives rise to a diversity of literature, poetry, drama, art, songs, expressions and oral tradition.

Shetlanders are proud of their distinct tongue: language adds layers to our culture, defining people and identity, enriching heritage and fostering pride in communities. Our distinct dialect contains a wealth of descriptors for our land and lives; from place names and crofts to flora and fauna.

Norn, once a fireside language, has been relegated to history as scattered phrases in old books held in dusty libraries. Its descendant, the Shetland dialect, continues to thrive, and its use is encouraged throughout the islands.

Ninety-five percent of Shetland’s placenames come from the Old Norse language

Shetland played a key role in the Shetland Bus operation

During the Second World War, Shetland again became an important northern base with around 20,000 servicemen heading to the islands to operate defences. Although these personnel were not all here at one time, there was a significant military presence in the isles throughout the war, and Shetland was a busy military base throughout.

The Shetland Bus operation took place during the Second World War, following the Nazis’ invasion of Norway in 1940. As part of the resistance movement, a series of daring missions began – across the North Sea to Shetland. These missions, many led by the Norwegian Leif Larsen, carried out by small, traditional Norwegian fishing boats, plied the North Sea throughout the wild winter months under the cover of darkness, and were a crucial part of the resistance.

These daring voyages ensured that refugees could escape Nazi-occupied Norway and that weapons, supplies and agents could be brought in. In the early years, Lunna, on Shetland’s east coast was used as a base and Flemington (now known as Kergord) House was the base for overseeing operations. However, it was soon recognised that better amenities were required to carry out essential repairs to the boats, and the operation moved to Scalloway in 1942.

Although further away on the west coast, Scalloway was an ideal location as it had a good shipyard and was quieter than Lerwick, which had a strong military presence. Losses were high during 1940-1943, but in 1943, the USA gave three fast sub-chasers to the operation, making it much safer for the crews. The Scalloway Museum has excellent displays about the operation, and visitors can see many of the buildings and slipway used. There is a memorial to the 44 men who lost their lives to the Shetland Bus on the waterfront at Scalloway and Remembrance services and wreath layings are held there twice a year on 17th May (Norwegian Constitution Day) and Remembrance Sunday.

Shetland Bus boat, Heland, visiting Lerwick in May 2025

Shetland Bus locations and displays:

Prince Olav Slipway, Norway House & Dinapore House, Scalloway

Kergord House/Flemington, Weisdale

Lunna House, Lunnasting

Scalloway Museum

Shetland Bus Memorial, Main Street, Scalloway

Ways you can support my work…