Lerwick a Potted History of the Growth of a Town

Victoria Pier, Lerwick. Photo: Alexa Fitzgibbon

At this time of year, when the days are getting shorter, and I undergo the daily ritual of opening all the blinds and shutters, only to close them again hours later, it makes me think about the place I call home and the town I call home: Lerwick.

Commercial Street, Lerwick. Voted second best high street in Scotland this month

This week Commercial Street was up for the ‘Best High Street’ in Scotland. It was voted second only to our neighbours in Kirkwall, Orkney, who scooped the top place. Anyone who has visited Lerwick’s main shopping street will understand why Lerwick ranked so highly. Paved with flagstones and filled with small, crooked buildings dating from the 18th and 19th century the town has a colourful and interesting past.

Shetland with Laurie's Lerwick walking tour. Photo: Susan Molloy

During the summer I offer guided evening tours through Lerwick that explore the old town, its buildings, its people, and all the stories associated with them. Without giving away too much of the tour, this blog will shed a little light into the history of our capital – and only – town in Shetland.

Lerwick is Shetland’s capital; home to about 7,500 people, almost one-third of the population. It’s situated on the east coast of the Mainland and is overlooked by the island of Bressay to the east.

Tours begin in the town centre at the Market Cross; I start by asking visitors to imagine they were standing at the same spot in 1600. I paint the picture; there are no buildings or houses and where the market cross stands was a small sandy beach with a gurgling fresh-water burn running down what is now Mounthooly Street (the lane beside the Tourist Centre).

Lerwick's Lanes are steep and narrow.

Scalloway, Shetland's former capital

Access to the foreshore was always a problem as Lerwick grew from the 1600s

Lerwick was not a natural choice for a town and, in fact, Scalloway (six-miles to the west) was the main town in Shetland until about 1838. Scalloway was an obvious choice; it sits at the foot of a fertile limestone valley, has a wide, natural harbour close to rich fishing grounds, and there is a good supply of fresh drinking water. Lerwick did not share these qualities, and the land where the town now stands was only ever used for grazing animals from the neighbouring township of Sound (which has now been swallowed up by the town).

The land, or cliffs, leading from the foreshore were steep and unforgiving and there was a limited supply of fresh-water. The narrow lanes leading from the main street, Commercial Street, up to the Hillhead are narrow and steep and, at one time were the main routes of access into the town centre.

But, what Lerwick – or Leirvik, (meaning the muddy or clay bay from Old Norse) – did have was a good, natural harbour. Bressay Sound, to the east, offers shelter from the winds, providing a safe and sheltered anchorage for ships. Without Bressay, there really would never have been a town here, Bressay provides the perfect buffer from the ravages of the North Sea.

The Dutch Connection

So how did Lerwick grow and develop to become the leading trading point in Shetland? From the 1500s Dutch fishermen, who went to sea in sailing ships called busses, began venturing north into Shetland waters in search of herring. We can think of their ships as ‘factory ships’ – herring were caught, gutted and salted onboard before being shipped back to Holland for further processing and sale. They began arriving with the advent of better methods of preserving and exporting herring for export. The money that the Dutch made on Shetland-caught herring went a long way in financing their wider exploits and the growth of Dutch trading colonies throughout the world and their catch was never processed onshore in Shetland.

In the very early days, there were no trade opportunities in Bressay Sound (or Lerwick), and the Dutchmen would come ashore and walk a few miles to the south-west to a spot near Gulberwick called the Hollander’s Knowe. Here they would trade with local people and exchange goods for fresh provisions and knitwear. This was relatively short-lived as, by the early 17th-century, entrepreneurial islanders were setting up shop on the shores of Bressay Sound – or Buishaven – bringing their products to the market.

It is around this time that the first real written account of the Dutchmen comes – although Shetlanders would have been familiar with the sight of their presence and their busses from as early as 1469. But, in 1615 a piece of legislation from Scalloway (the then capital) banned all trade within Bressay Sound (Lerwick was yet to be named), and all the temporary trading booths that lined the foreshore were ordered to be razed to the ground. These buildings would have been no more than a collection of small wood or stone huts, but regardless of type and size; they were destroyed. It was believed that this trade, and the interactions between the dutch fishermen and local people, was in some ways illicit and seedy and law-makers went to great lengths to try and stamp out what they saw as the deplorable behaviour by islanders.

The first time the name ‘Lerwick’ was mentioned was in a similar proclamation, again, from Scalloway, 10 years later in 1625. This legislation stated that Lerwick was a lawless place filled with drunkenness, debauchery, murder, theft and prostitution; it was again ordered to be destroyed. One clause, in particular, is notable and very telling of the times; this clause said that women were not to attend the foreshore under any circumstances and that if they did have any knitwear to sell, they were to send a son, brother or husband to do their bidding for them. There is scant evidence that women played any more deplorable a role than their male counterparts, but they were singled out as a specific problem and root cause of much of the scandal surrounding the foreshore.

At this time Britain fought three wars with the Dutch. Several attempts were made to build a fort of sorts in Lerwick at various points during these wars (1652; 1665 & 1673) and it was burnt down twice by the Dutch. Fort Charlotte, that still stands today, was finally completed in 1781 and is named after Charlotte, wife of King George III’s wife. It’s an interesting fort; similar to Fort George in Inverness, being shaped like a pentagon with five-sides, much of its grandeur is now indistinguishable as the town has more-or-less swallowed it up in a bid to find space to build.

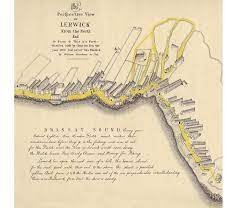

Despite wars against the Dutch and a sustained effort from Scalloway to impede trade, the town grew, and by 1766 when William Aberdeen drew his map of Bressay Sound, there were a good handful of substantial stone-built houses lining the rocky foreshore, all built gable on to the sea, maximising every square inch of foreshore available. Aberdeen describes the scene at the time:

“Every year between eight or nine hundred Dutch vessels make their rendezvous here before they go to the fishing, and was it not for this Dutchmen, the town of Lerwick would soon decay. The Dutch leave peas, barley, cheese and money for stockings.”

The fishing boats would appear every year in their hundreds and moor in Bressay in preparation for the commencement of their summer herring fishery. This fishery always began around midsummer, on 24th June, or the Feast of St John the Baptist. This date, known as Johnsmas in Shetland, was traditionally an important calendar date.

George Low, visiting in 1774, commented on the commendable architecture springing up in this new town. He said that Lerwick had “been much improved by several handsome houses built in the modern style.” But not all reports were good, and for many, Lerwick was seen as a place of loose morals and degradation. The Reverand William Watson wrote a scathing report in the New Statistical Account of 1834-1845. He described the kind of life that you might find in Lerwick, and of the people who frequented the area: “They think they will be free of voar [spring] and harvest labour; and after having spent, in Lerwick, what little they have saved here, return [to their original community] destitute, and are glad to get a piece of land, probably much inferior to what they possessed years before.”

But that said, Lerwick did offer up opportunities for Shetland’s growing merchant class – working men who were finding wealth and prosperity – legal or otherwise – in Shetland’s new and burgeoning metropolis.

It is a well-versed fact that much of Lerwick grew due to the illicit trade in gin, brandy and tobacco and that, smugglers founded the town. As well as all the legal trade that took place between Shetlanders and the Dutch fishermen who came ashore, there was a high proportion that was of course, illegal. Evidence of this can be found under Commercial Street, from Harry’s Department Store at the north end of Commercial Street to Leog at the south end, there are a series of underground tunnels; many of them are still there, some have collapsed, and others were filled in during building works. Illegal goods – gin, brandy and tobacco – were unloaded from the ships and squirrelled away underground to avoid customs. Duty had to be paid on goods such as tobacco, spirits, tea and timber but, quite often, boats would fail to declare their cargoes, or they would attribute them to non-taxable goods in order to avoid excise. There is no doubt that trade – legal or otherwise – form the very foundations of the town.

Smugglers' tunnel under Commercial Street

A small door that led to a smugglers' tunnel, Lerwick

My Top 3 in the town centre:

The Tolbooth

One of the first stops on the tour is at the Tolbooth, overlooking Victoria Pier, built in 1770 it was designated for collecting taxes, and over the years it has had a colourful and varied past which I talk about more on my tours. Of its numerous uses, it has been; a jail, ballroom, museum, archive, seaman’s mission, post office, and more recently, the headquarters for the RNLI (Royal National Lifeboat Institute).

The Lodberrie

Another firm favourite with visitors and locals alike is The Lodberrie; instantly recognisable by many visitors as the home of Detective Inspector Jimmy Perez in the fictional TV crime drama Shetland. This building, dating to about 1772 was one of 21 lodberries that lined the foreshore in Lerwick by 1814. The word lodberry comes from the Old Norse hladberg and means ‘a landing place, or a landing stone’ and describes the type of use these utilitarian – yet beautiful – buildings were designed for. Ultimately these were trading booths, built with their foundations in the sea. Winches unloaded boats that could be berthed alongside and legal goods were then sold from street-side shops, and the illegal goods were taken into the maze of tunnels that ran underneath the street – and feet – of the customs men.

James Stout Angus, who grew up in Stout’s Court, wrote about a kokkilurie (daisy) that grew near his home, written in the dialect, his poem is evocative and pure:

“Dey wir ee peeire white kokkilurie at grew

At da side o da lodberry waa;

Hit wid open hits lips tae da moarnin dew,

An close dem at night whin da caald wind blew,

An rowe up hits frills in a peerie roond clew

As white as da flukkra snaa.

…

“In October, ee nicht he cam on ta blaa

Wi a odious tömald o rain,

Da spöndrift cam in ower da aest sea waa

An drave trowe da yard laek do moorin snaa;

Neist moarnin my peerie white flooer wis awa,

An vever wis seen again.”

Bain's Beach, the only remaining part of virgin foreshore in Lerwick's town centre

Bain’s Beach

A favourite of mine, this is the only part of virgin foreshore that remains in Lerwick's town centre. The golden sand is a surprise in the middle of town, and it always takes me right back to my childhood, conjuring up memories of eating fish suppers on a summer night when the tide allowed access to the beach. Because there was so little available land for building on the shoreline, much of the centre of town, including the Esplanade and everything that stands east of Fort Charlotte, has been reclaimed from the sea, drastically altering the natural shoreline.

Shetland with Laurie walking tour. Photo: Susan Molloy

Dutch fishermen continued to use Bressay Sound as a rendezvous point before the commencement of their summer fishery (24th June) right up until around the First World War, after that their busses were replaced with more modern ships and the trade dwindled off.

The Dutch influence in Shetland is still remembered today. At the Knab in Lerwick, a headland cliff on the approaches to Lerwick Harbour, there remains a spot known locally as the Dutchman’s Leap. This is said to be the spot where a Dutch fisherman and his pony fell to their deaths from the cliffs. It wasn’t unusual for the fishermen to come ashore for exercise, the boats were always accompanied by a doctor who encouraged them to go ashore for exercise. Locals would, in turn, charge them a stiver a mile for pony rides between Commercial Street and the Knab. On this particular occasion, the pony was spooked and went careering off the cliffs.

On the island of Papa Stour there’s a freshwater loch called the Dutch Loch, this is said to be where the Dutchmen would come ashore to wash their clothes.

A new era

Despite the dwindling number of Dutch fishermen, Lerwick, as a result of their arrival was now firmly established. By the 1830s Lerwick was very much seen as the capital of Shetland and proclamations began to be read from the Market Cross on Commercial Street rather than from the gates of the Scalloway Castle.

The home fleet (Shetland-owned boats) too was growing and now Shetland had a thriving fishing industry. This locally-based fishery caused another boom time for the town. In the early 1900s herring, even without the Dutch, was still big business and local boats – and those from the north of England and Scotland – were chasing the silver darlings. This fishery caused the town to burgeon yet again as many incoming workers flocked to Shetland for the summer herring season. For the first time, the catch was being processed and shipped from Lerwick, rather than being taken away on rudimentary factory ships, or busses. With the industry rooted in Lerwick, there was a considerable growth within the town as factories sprang up with all the associated barrel-makers and accommodation blocks to house the workers.

Lerwick has seen many changes and improvements over the years from its humble beginnings as no more than a trading outpost. Some of these changes have been better than others and only history will tell us how today’s actions will shape tomorrow’s future.

Among the most important, if least glamorous, of improvements were work on implementing drainage and sewage systems. These systems revolutionised life in the town, improved health and gave higher appeal, attracting more people of class to want to stay within the town boundaries. These schemes were introduced in the 1870s; at that time the town was described as filthy and diseased, with open sewers running down the lanes to the sea. Key to implementing these changes was a man called Charles Duncan who lived in Leog House. His forward-thinking ensured that the town was able to grow out of the chaos and disorder that characterised its early beginnings.

'Pavement graves' in the Lerwick Lanes (note the cross marked on the flagstone). Photo: Susan Molloy

Much of the town has been altered, re-built or adapted. One of the best examples of how great changes were carried out is where the current Church Road now stands. Today this is the main road that leads up from the Tolbooth (on the waterfront) towards St Columba’s Kirk. At one time Church Road was known as Sooth Kirk Closs and it was lined with overcrowded houses. It was densely populated and the houses stood in poor condition. In the 1960s the houses were torn down to allow the new road to go in, allowing better access to the town centre. At the same time, the graveyard that sat between Sooth and North Kirk Closs was removed – and turned into a car park – with the council advertising in the local paper, asking people to kindly collect their relatives. If you walk around the area, particularly around the Masonic Hall, there are still paving slabs marked with a simple cross, indicating the spot of a previous grave. Whatever the rights and wrongs, it did allow much-needed access to the town centre.

By the 1880s the town had reached the top of what is now the Hillhead; it was a busy, overcrowded and squalid mess. There was no urban planning, just entrepreneurial locals trying to carve out their corner of this new town which had so much offer and promise to the rising middle classes.

Finally, in 1883 Lerwick’s Town Hall was built, immortalising the town as the capital and main seat of power in Shetland. Built in under a year, the Town Hall is a grand sandstone building with ornate carvings, stained glass windows. Sandstone was quarried from the neighbouring island of Bressay to build the main structure and the finishings were made using imported sandstone. The clock tower dominates it – an addition not on the plans that were drawn up by architect Alexander Ross, but added by local builder John Aitken who had his own personal vision for the town’s most famous landmark.

When it was built, locals complained that it faced the wrong way – the front of the building faced empty fields and had its back on the town. When it was built, Lerwick didn’t extend beyond the Hillhead where the Town Hall stands.

The reason for this is because one forward-thinking town councillor said that it faced the new town of Lerwick that would follow – and it did. Lerwick continued to grow rapidly throughout the late 19th and early 20th century and, as predicted, the Town Hall faced the ‘New Town’.

The original plans for Lerwick's Town Hall

Lerwick was built on the fishing, and it is those deep roots that keep it thriving today. Today Lerwick is one of the top fishing ports in the UK; with a flourishing industry, a new state-of-the-art fish market and new boats arriving year-on-year to make up the fleet. I am very proud of the place, and town, I call home.

If you would like to book a walking tour with me, please email and get in touch, tours will be running between May and September on Wednesday evenings. For info please email info@shetlandwithlaurie.com.

With love,