Shetland’s contribution to modern medicine

Recently, I was asked to deliver an after-dinner speech for the Viking Surgeon’s Association which was held in Shetland in September. It was a real honour to be asked to address the group — if a little daunting — and I thought I’d share my speech with you.

What a pleasure it is to be here with you in the beautiful setting of Lerwick’s historic Town Hall – I'll come to that later – but first, as surgeons, you are the unsung heroes of modern medicine. You possess the extraordinary skill to mend what’s broken and to restore health. But tonight, I want to remind you that while your work is often invisible, its impact is profoundly felt.

In Shetland, and throughout rural areas, our surgical team stands as guardians of life in their own right. Here, in our more remote regions, you embody resilience, adaptability, and excellence.

Tonight I want to speak to you about the islands – and maybe a little of its medicine too.

Shetland, as you may have already noticed, is neither Scottish, nor Scandinavian – we sit somewhere in between, culturally and physically, with the Shetland flag flying proudly from this very building. I always tell the tourists, to their initial disappointment, that they won’t find any haggis, kilts and bagpipes here, but what they will find is a culture deeply rooted in its Viking past.

Shetland has only been part of Scotland for around 550 years – a statement that always raises a chuckle from our American guests, who believe this to be ancient history, but for an island which has been inhabited for 5000 years, this is only yesterday in historical terms.

The room we’ve dined in is laced with nods to our Scandinavian past, and the window at the back of this hall shows two people, and a marriage.

This marriage was a turning point in our history, and marked the end of almost 600 years of Scandinavian rule. Since the Vikings came here, around 850 AD, Shetland became part of their wider kingdom, adopting their language, cultures and law – in fact, if you visit Unst, you’ll find a landscape that has a greater density of Viking longhouses than anywhere else in the world, including Scandinavia!

The ‘marriage’ window in Lerwick Town Hall

The unfamiliar place names found in Shetland all have their roots in this old language which was once the fireside language of the islands, but has now been mostly relegated to dusty old books in museums and archives. This language was a form of Old Norse, called Norn, and we still find it in the dialect spoken here today – I promise to try and speak my best English tonight, but I will share one or two medically-inclined Shetland words with you.

Spaegie – muscle fatigue after exercise

Hansper – muscle aches

Gulsa – jaundice

Brunt-rift - heartburn

Doitin – mentally confused, or dementia

Poor aamos – frail

And the favourite – peerie (which means, small)

This language came to Shetland with the Vikings when they arrived here about 1,200 years ago. Prior to this, we have no record of what the language looked like or what the place names were. The Norse settlers rewrote the map and changed the course of Shetland’s history entirely. We will never know what pre-Norse language in Shetland looked or sounded like, the Viking assimilation was a wholescale cultural transformation.

Old Norse was spoken across the Scandinavian world and the closest surviving language today is found in Iceland. Each country had its own version of the language and in Shetland, this developed to become Norn and it‘s where the roots of our language are firmly planted.

Shetland’s language persisted until a few hundred years ago and, by the late 19th century, there were very few native speakers remaining. Faroese scholar, Jakob Jakobsen, who came to Shetland at the end of the 19th century, recorded all the Norn words he heard spoken, and those that could be remembered. He travelled all over the islands and compiled these words into a two-volume dictionary of over 10,000 words on the Shetland language which remains, to this day, the greatest work on the dialect ever undertaken.

Scandinavian rule came to an abrupt end in 1469 when King Christian I of Denmark pledged us to Scotland, along with Orkney — although we hung onto the language and customs of Scandinavia for much longer. This transfer to Scotland happened when King Christian I was set to marry his daughter, Princess Margaret, to King James III of Scotland. This was no great love story, and it was very much a marriage of convenience to secure peace between nations. He couldn’t afford the wedding dowry, so gave us away, with the intention to buy us back at a later date. This never happened, and we have remained part of Scotland, ever since.

Rather insultingly, we were given away at a pittance of the value placed on neighbouring Orkney which was, and is still is, far richer agriculturally.

Those two faces in the glass (pictured above) are Princess Margaret, and King James III and it shows their union. 500 years later, our island flag was developed, celebrating 500 years of Scottish rule, and it shows the Nordic Cross and the colours of the Scottish saltire.

Despite what is often believed, Shetland is not a faraway backwater, remote from the rest of the world, and we have always sat on important trading routes within the North Atlantic. Today we look at maps and focus on the urban centres, Edinburgh and London, but in the past, Shetland was a gateway to other lands — we sit closer to the Arctic Circle than London and 200 miles from Aberdeen to the south, Norway to the east and Faroe to the northwest. From Faroe, Iceland is only another 200 miles northwest.

Our islands have seen ships from the Dutch East Indie company and Spanish Armada come a-cropper on our shores. We’ve seen whalers from Hull and many hundreds of Dutch fishermen who caused the town here in Lerwick to exist and thrive.

Lerwick’s historic heart and Bain’s Beach

Hundreds of Dutch fishing boats came here from the 16th century – their vessels would congregate in Bressay Sound – what is now Lerwick Harbour. These fishermen provided excellent trade opportunities for locals who came to trade their knitwear and fresh provisions, in exchange for brandy, gin and tobacco. It is said that Lerwick was built by smugglers and under Commercial Street, a maze of tunnels connect buildings, and were designed to smuggle contraband away from customs men.

Scalloway, six miles to the west, was the capital at this time — and they didn’t like what was happening here in Lerwick, ordering it to be burnt to the ground. One piece of legislation from 1625 is very telling of the time and also stated that women were not permitted to attend the foreshore as it was feared they were selling more than just their stockings — perhaps they were also selling hats and gloves. Who knows.

But Lerwick grew from the ashes, and by the mid 1800s it was the island’s main economic centre, and became the capital — It was a squalid and dirty town where open sewers ran down to the harbour and infectious disease was rife. It was a fishing port, a whaler’s stop, and a very unsavoury place by all accounts.

But Shetlanders have always had an entrepreneurial spirit, and a make-do-and-mend attitude that has allowed them to thrive and this is a time when we see some of Shetland’s greatest contributions to modern medicine.

Johnnie Notions house in Northmavine

Johnnie Notions

In the 18th century, smallpox would tear through communities here, killing up to one third of the population on each calling, and one man, John Williamson, made a tremendous contribution to the islands, saving thousands of lives in the process.

John Williamson, better known as Johnnie Notions, was a self-taught man. A seaman and weaver to trade, he had a keen interest in medicine. He lived in the North Mainland at a time when smallpox frequently ripped through communities, brought in by seamen.

It began in 1700 when a young man came home to Shetland from the Scottish Mainland, passing through Fair Isle on his way back to Lerwick. He was suffering from smallpox. Smallpox was a new disease in Shetland, and Shetlanders had no immunity to it. It spread like wildfire. The Fair Isle people began to sicken and two-thirds of them died. It spread through Shetland quickly, with ministers declaring that ‘the dead lay in every corner’.

Shetland was unusual in its experience of what they called the ‘Mortal Pox’ in that it killed more than just the young and very old. Communities were left without healthy breadwinners — without fishermen to man the boats, women to work the fields and tend the young and elderly, and men to bury the dead.

Smallpox was to return again with vengeance in 1720, 1740 and 1760.

Johnnie Notions was born around 1730 and survived the pox of 1740.

In 1721 Dr Charles Maitland inoculated an infant in London and in 1796, Jenner inoculated an 8-year-old with material from a cowpox sore on a milkmaid's hand, but there is evidence that Johnnie Notions was successfully inoculating here in Shetland throughout the 1770s and 1780s and, by the 1790s, he was well-known locally.

Most doctors in Shetland relied on the traditional methods for dealing with smallpox victims. They recommended the so-called hot treatment: a blazing fire, multiple blankets and as little fresh air as possible — this was later described as a ‘murderous’ method.

John Williamson began to dabble in inoculation in the 1770s. No record exists of when he first took up his scalpel. Contemporary documents indicate that Williamson was inoculating in the late eighties and early nineties, but there can be little doubt that he had begun his trade long before that and, by the 1790s, he had acquired a remarkable reputation in Shetland.

Many inoculators used their inoculating matter right away, but Johnnie Notions had come up with the idea that it would be less dangerous if he stored it before use. ‘To lessen its potency’. He dried it in peat smoke, and then buried it with camphor (an organic matter from trees, commonly used in creams and ointments). Peat is known for its antiseptic properties — and has reportedly been used to clear the womb of unwanted pregnancy — and Camphor’s antibacterial properties prevent the matter from going off.

The next step was the inoculation itself. Williamson rejected the lancet, and made his own knife. With it he made the smallest possible incision in the outer skin of his patient’s arm, without releasing blood, and inserted a tiny amount of matter. ‘The only plaster he used, for healing the wound, was a bit of cabbage leaf’.

John Williamson was a successful inoculator. The minister of Yell reported that Williamson had inoculated several thousand people, and that he had never lost a single patient

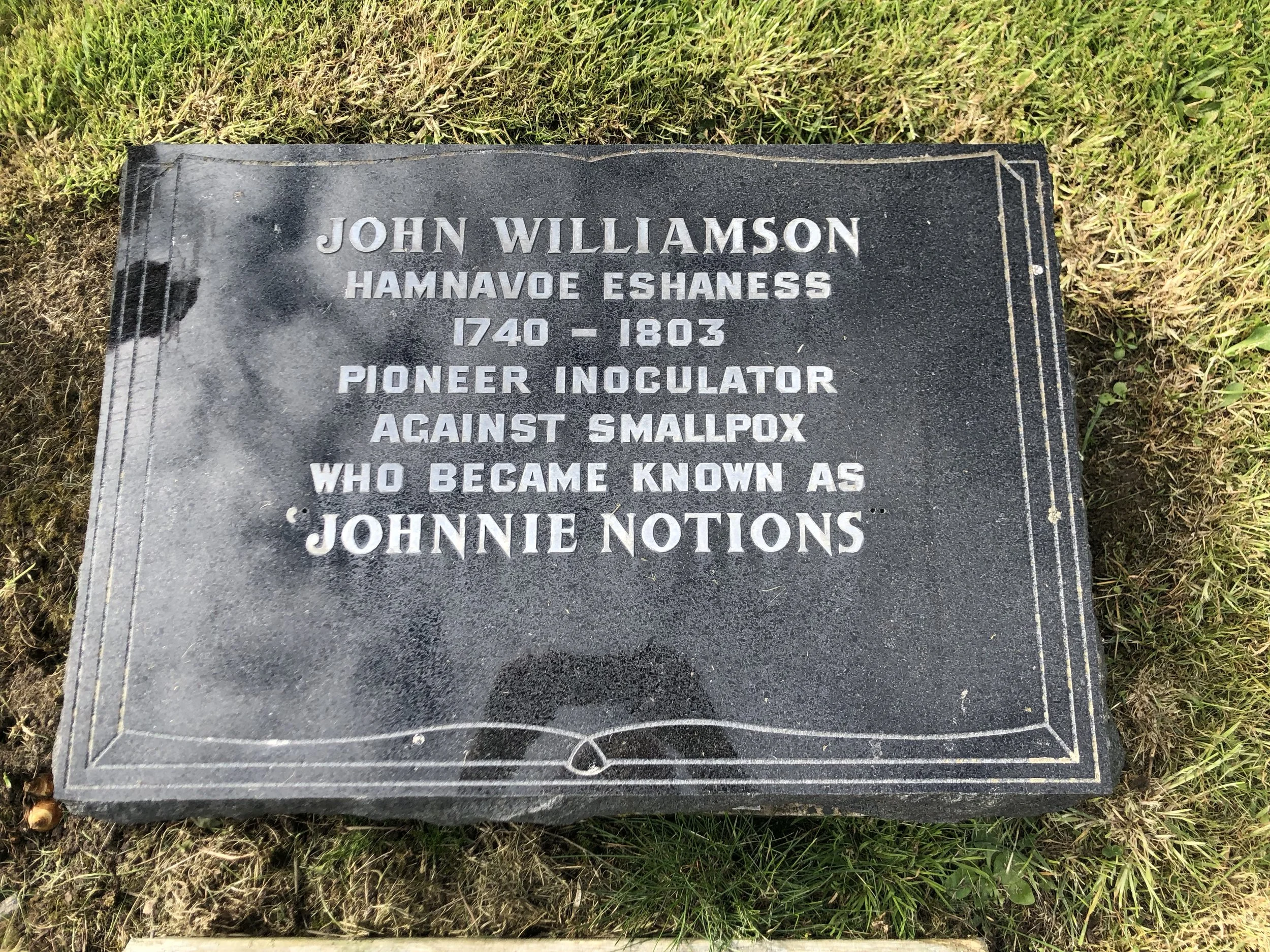

And if nobody believes he was the inventor of the smallpox vaccine, you can head to Eshaness and read it in writing on his very headstone!

Sir Watson Cheyne

Another great contribution was made by Sir William Watson Cheyne from Fetlar. In the 1920s, when many rural areas had little or no medical provision, Fetlar was home to one of the most eminent surgeons of Victorian and Edwardian Britain.

Sir Watson, as he was known locally, was a surgeon and bacteriologist, who, alongside Joseph Lister, dedicated his life to the development of antiseptic surgery — to which I’m sure you’ll all be well acquainted with!

He served alongside Lord Roberts as Consultant Surgeon in the Boer War, where his experience on the treatment of wounds was invaluable — although carrying out surgery in the open field amongst dust storms must have been challenging, even for the experienced Sir Watson.

Sir Watson served during the First World War and spoke emphatically about the importance of sterilising wounds quickly and was critical of surgical practice at the beginning of the War — his feeling was, that 50 years after Lister recognised the cause of sepsis, surgeons were still not being taught it in medical school, or practising it in the field.

Home of Sir Watson Cheyne, Fetlar

Folklore

Sir Watson grew up alongside a backdrop of 19th century superstition where medical provision was often based on folklore and treated with natural remedies.

His challenges weren’t only based on the medical profession adopting his knowledge and skills, but also the culture within the "common people” who relied on wise women and superstition to treat ailments. People were deeply god-fearing, and ministers often stepped in with their own medical advice and bibles to ward off evil.

One description of curing consumption involves smearing patients with mould from the last body buried in the kirkyard or drinking water from under a bridge where the last coffin passed — and often ministers would deliver emergency care where needed.

Gulsa — or jaundice — was treated by the gulsa whelk, or garden snail, and sprains were treated by tying a series of knots in a thread and muttering a charm or spell.

When a woman was about to give birth, a black cockerel could ward away the trows — a race of little people who lived in the hills — and it was believed that women in childbed were particularly vulnerable at this time to trows who would take away their healthy baby, leaving an ailing or sickly changeling in its place.

Modern times

But as the 19th century drew to a close, things were improving; the 1886 Crofters Holding Act brought security of tenure to crofters for the first time, and houses were improved now that the threat of eviction from the laird didn’t loom over tenants' heads. Living conditions improved and, bit by bit, medical care became more widely available to islanders.

Superstitions still persisted — trows were still blamed for unexpected infant deaths, and customs such as leaving a bible out to ward them off was often seen as the best defence against disease — but Shetland was slowly moving into more modern times.

Here in Lerwick, the town’s sanitation and drainage were installed, cleaning up the streets and lanes, preventing much disease and death and the first Gilbert Bain Hospital opened in 1902 — it’s now the funeral directors, not a reflection on our medical professionals, I’m sure!

In 1883 this building (Lerwick Town Hall) was opened — and by this time, Lerwick extended up to the top of the hill here, the Hillhead, and the Town Hall faced green fields. Local people criticised the design, saying that it faced the wrong direction. But local town councillors defended it, saying that it faced the future, and that the future lay to the west. Turns out, they were right, as Lerwick now extends far beyond the reaches of the Hillhead and this building.

As we enjoy the evening and celebrate our own rural communities, let’s also take a moment to appreciate the journey that brought you here. Each of you has a story—stories of dedication, of overcoming obstacles, and of the relentless pursuit of excellence. These stories are a testament to your commitment to improving lives, and they deserve to be celebrated.

So, let’s raise a glass to the unsung heroes of medicine, to the surgeons whose skill and dedication know no bounds, to my absent gallbladder, and of course, to the breathtaking beauty of Shetland, which reminds us that even in the most challenging environments, excellence, compassion, and cutting-edge medicine can thrive.

Ways you can support my work…