Our boys need sox: How Shetland women knitted their way through the First World War

Over one hundred years have passed since the First World War was declared. Much of the coverage is often focused on the courage and bravery of the men who fought for King and country. The following is the first in a three-piece research piece which is based on a piece I wrote a few years ago for the Wool Week Journal. It highlights the knitting that Shetland women did to aid the war effort. This first essay will consider the personal requests for knitwear from the front-line to women in Shetland.

Women, unable to join up for fully-fledged military service were crucial, nonetheless, to the war effort. Stepping into men's shoes on the Home Front, women worked hard to maintain 'business as usual' on home shores.

Shetland women were well accustomed to taking on the role of men for prolonged periods. Traditionally, Shetland men went to work at sea; at the fishing, whaling, mercantile marine or, in more recent years, offshore oil and gas. Women have long been expected to take on the extra burden of work at home and on the croft.

It is the story of women during the war, which, for me, demonstrates how the nation rallied together to secure victory. I am by no means saying that women won the war, but what they did do was ensure that life at home continued as usual, and in their own modest way they were able to offer comfort to many of the men serving overseas or laid up in hospital as a result of injuries sustained through war.

At a local level, Shetland was by no means immune to war, about 3,600 men served – 600 of whom never returned home. These losses were felt in communities across the isles; no parish was spared the grief following in the wake of the war. Seventy per cent of Shetlanders served in the Royal Navy or as merchant seamen, while the remainder volunteered, or were later conscripted into Army regiments in Britain and the Empire; joining the offensive on the Western Front and beyond, where trench fighting was the most common – and brutal – method of combat.

Remembrance Day service at Lerwick's war memorial.

As well as taking on the hard work on the croft – ensuring animals were tended, crops grown and peats cut – Shetland women also provided provisions for 'comfort packages' which were sent to troops serving on the front line, those who were wounded and Allied prisoners of war.

Comfort packages contained non-perishable food items, tobacco, and clothing – especially knitted garments such as socks, scarves, balaclavas, cardigans and gloves.

Thomas Manson, the editor of the Shetland News, said that 'in this work, the women of Shetland set a magnificent example' determined 'to do all they could to make the lot of the sailors and soldiers more comfortable.'

The joy of socks

The most important of these knitted items were socks. Given the filthy conditions facing men in the trenches, these were also the most welcome. The cold, wet and muddy environment of the trenches meant that hygiene was a challenge for the men, and the resulting trench foot was a constant and painful problem.

Trench foot is a fungal infection, which, if untreated causes gangrene and, in the worst cases, would lead to amputation of the foot and part of the leg. During the harsh winter of 1914/15 over 20,000 men in the British Army were treated for trench foot. The only remedy was for soldiers to dry their feet and change their socks several times a day – this was often impossible in the trenches, given the filthy, crowded conditions. By the end of 1915 soldiers serving in the trenches were ordered to have three pairs of clean, dry socks with them at all times and were under strict orders to change their socks at least twice a day.

In response to this order, many thousands of pairs of socks were knitted by British women and sent to the front. The campaign continued throughout the war years. When America joined the war in 1917, so to did the catchy slogan, 'Our Boys need Sox: knit your bit'.

The importance of dry socks was not only encouraged by medical and military officers; it was further promoted amongst the men on the ground. Trench journals such as the Port Lincoln Bully-Tin provided humorous anecdotes and 'hints' for recruits, including the recommendation that 'every man should have a dry shirt and dry socks always in hand ready to change when necessary'.

The gratitude of receiving a pair of socks is highlighted in the personal letters in Shetland Museum & Archives sent home from troops. Soldier C. Willett writes to Chrissy Leslie of Sandsound of his gratitude. The letter, addressed from

'Somewhere in France' says:

Dear Miss Leslie

Just a few lines thanking you for the pair of socks you so kindly knitted. I happened to be the lucky soldier who received them. These socks came in very acceptable, and I am very sure that the kindness of the Shetland girls is fully appreciated by the boys in this regiment.

I do not know what sort of weather you are having in Shetland, but out here is simply grand sun shining all day long, it is quite warm. I expect we shall have some bad weather shortly to make up for this spell of sunshine.

Will now close, again thanking you and hoping to hear from you again shortly.

Kindest regards,

C. Willett

In another letter, dated 1st January 1918, Peter Leslie from Sandsound asks his sister, Chrissy, if she would kindly send him some gloves and socks:

'We are still having frosty weather', and the 'ground is as hard as stone'.

He says that his regiment is still in France but that they have recently been pulled back from the front line to allow the men the opportunity to rest. In another letter, he writes:

'I wrote you last week about sending a pair of gloves and sox. You can send it as soon as you can'.

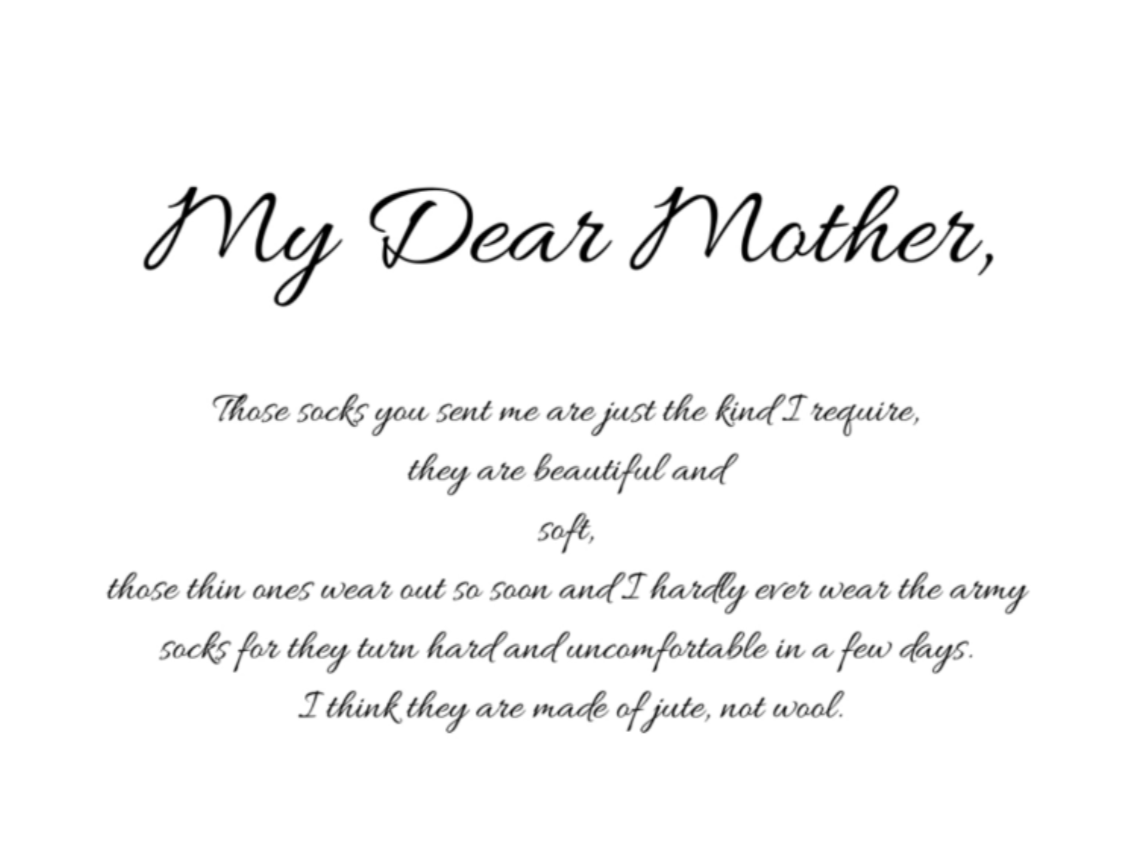

Lerwick born, Karl Manson in a letter to his mother dated 27th August 1916 writes:

Karl never returned it home; he was killed on 9th April 1917 by a sniper, aged 19.

(You can read more about that in a blog I wrote, here.)

These personal letters show a request to a loved one for knitwear but organised drives and appeals were established too. These drives saw many thousands of garments sent to army and naval personnel; to thousands of faceless names spanning the Western Front and beyond.

This was the first in a three-part series; the next part will be publishednext Friday, 2nd October.

With love,

“Visitors want to have the best experience; they want to see Shetland through the eyes of a local. They want to taste the salt on their faces, smell the sea and bear witness to the wind in their hair. They want to drink in the sights, the smells and the sounds of an island community. They want to be shown the places they would otherwise not discover. They want to piece together the fascinating jigsaw and truly discover Shetland; this is the trip they have dreamed of.”